In schools, the philosophy and context of the place and time, and the skills and dispositions of the administration and the teachers, all set the stage for the kind of teaching and learning that will evolve. For creativity to be central to teaching and learning, teachers must honor the students’ intelligence, way of approaching life, and their innate drive to learn. In the schools of Reggio Emilia, Italy, and in any classroom where hard work, joy, excellence, respect, and creativity abound, the students and teachers make their way together in a learning journey. The teachers are not handing over information that they expect the students to memorize and repeat.

To create well-being for everyone, the classroom needs to be organized and clean and the teachers need to be kind and present for the children. The routines and the agreements of the classroom can be thoughtfully authored, shared, and owned by each person, rather than imposed by the teachers on the children as rules.

In the schools of Reggio Emilia, teachers place a high priority on listening to children. They often do so in the context of conversations based on open ended questions without a “right” answer. The teachers seek to uncover children’s way of experiencing and noticing the world around them as well as their way of making sense by putting new ideas together.

At Harwood Union High School, the teachers and administration have dedicated themselves to Socratic Seminar and the Harkness Method. Students come prepared to enter into dialogue about what matters and what is most compelling about what they are reading and learning, rather than to listen to teachers lecture about what is most important.

Our friend and professor emeritus at Middlebury College, John Elder, most often engages in what he calls inductive dialogue, (rather than deductive), with students about poetry and text. He says, “Let’s start by talking about what we notice and see what happens, rather than starting with the main idea that the professor wants to get across.”

All of these are ways to bring creativity to the center of teaching and learning, but also to life long learning. This is a way to approach learning that respects the intelligence of students and their need and right to make their own meaning which might come as a surprise to us as teachers. How wonderful!

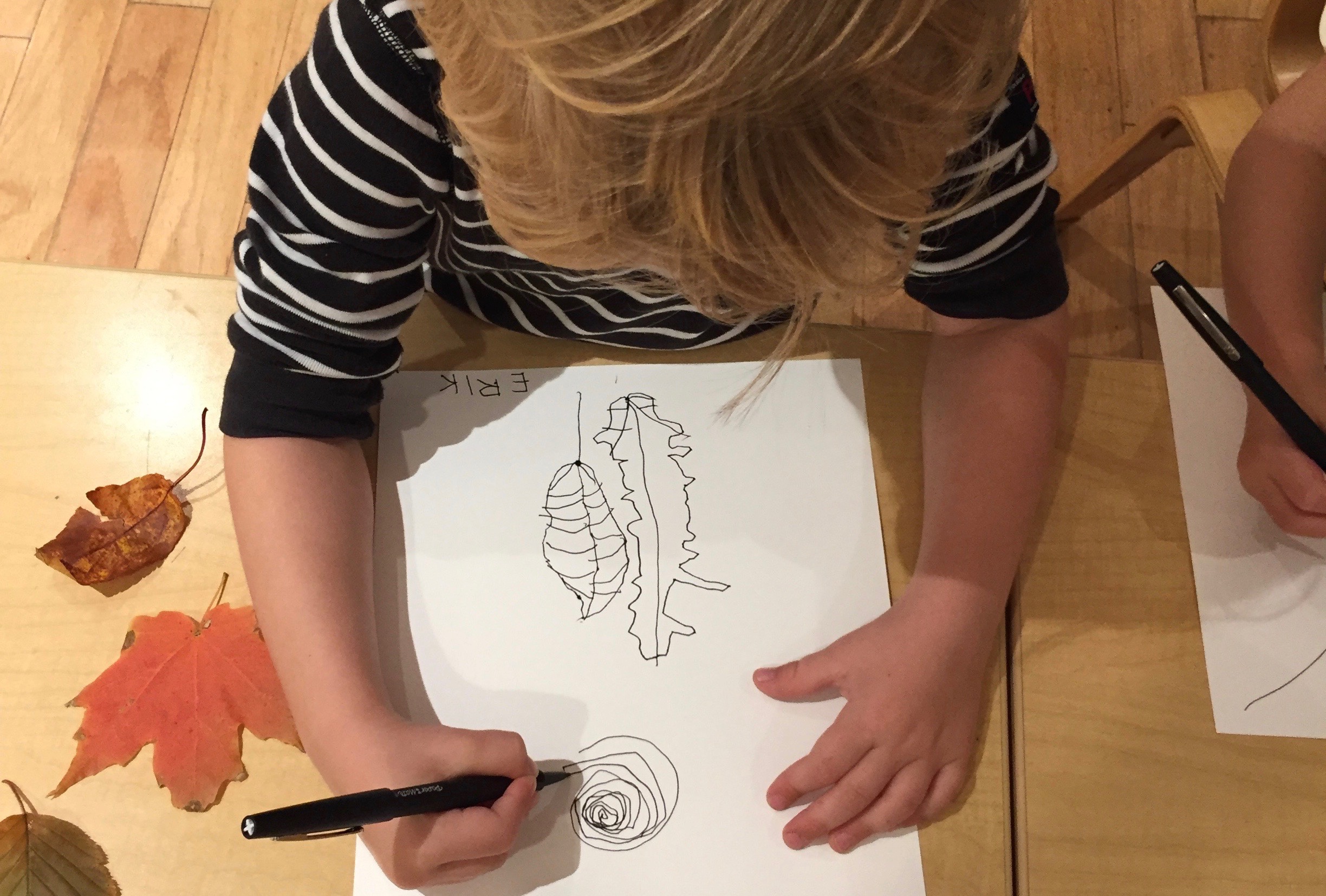

Another way to nurture creativity in the classroom is to bring in materials and to offer multiple ways to express ideas. The educators in Reggio Emilia use the term “the hundred languages of children” to refer to all the disciplines. They prefer to call them languages (rather than disciplines) in order to emphasize the communicative power of math, science, clay, paper, gesture, music, words…Project work that includes multiple languages can become, as Ron Berger writes, beautiful work. In An Ethic of Excellence: Building a Culture of Excellence with Students, Ron advocates for the power of a culture of excellence in every classroom. In the context of this kind of “culture of excellence,” students strive to create beautiful work in graphics, writing, math, science. All of this takes effort, skill, understanding and multiple drafts executed within the structure of a supportive and skilled community of learners. This work is most often composed for a public audience and contributes in some way to the larger community.

In an article in Educational Leadership in the issue on Creativity, Carol Ann Tomlinson writes:

Don't consign creativity to the realm of fairy dust. Certainly, moments in the creative process seem to come from beyond us, almost magically. Those moments, however, are nearly always preceded by long periods of sweat and grit. Perhaps the single most common attribute of creative people is how hard they work. They know a great deal about their domain or discipline. After all, people are creative in some pursuit—writing, soccer, botany, or marketing. Help students develop what Ron Berger calls an ethic of excellence—hard work, pride in craftsmanship, and appreciation for fresh, fruitful thinking.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi devotes the last chapter of his book, Creativity: The Psychology of Discovery and Invention to personal creativity or what James Kaufman and Ronald Beghetto call "little-c creativity”…everyday creative efforts. Among the strategies that he suggests that are most helpful for classrooms are:

• Shape your space…curate your space (classroom) so that you are surrounded by order, the tools that you need, and personal meaning.

• Take charge of your schedule…you (your students) need the time and discipline to devote to what you love, to the work that you seek to accomplish.

• Take time for reflection…relax, pause, take some time out from rushing from one thing, (class), to another.

• Look at problems from as many viewpoints as possible…look at situations from various angles, consider different reasons and causes, try tentative solutions, reformulate the problem.

• Find a way to express what moves you…creative problems generally emerge from areas of life that are personally important.

One of my favorite memories as a fellow in the schools of Reggio Emilia after a morning with children in all their various groupings, is the flurry of activity among the teachers. Teachers would gather in the atelier and tell each other what had happened with words like…you would not believe what Filippo and Giorgia invented. I can’t wait for you to see what Andrea constructed. Story after story of surprises around what happened…what the children did, said, made, created, solved, and wondered. Their excitement and collaboration around learning and creativity for themselves and alongside the children has always inspired me.

Creativity can flourish when there is a context that also includes, as our friend John Elder says, buoyancy and playfulness, presence and gratefulness. Creativity needs friends, fertile ground and good care just as we all do, and most especially, our children.