The West Yard, campus at A Child’s Place

About a month ago, I was at my grandson, Jack’s, preschool, A Child’s Place, in Lincroft, New Jersey. I had agreed to offer a professional development morning and planned it in collaboration with the director, Zach Klausz, and a small group of teachers. A Child’s Place is a Reggio-inspired school founded by Alba Di Bello. I met Alba some years ago at an education conference and was happy to discover that my grandson would attend the school that she led for thirty-four years. Zach and the teachers at A Child’s Place and I decided that reading Bringing Reggio Emilia Home over the summer would be a good way to prepare for my day with them. I organized the morning and my slide presentation around some of the themes from the book: the learning community; dialogue, conversations and listening to children; the hundred languages of children; and project work.

I structured the presentation so that after each theme, we could think together about what resonated with them, their practice, and where they saw that they might expand and grow their practice with children.

We met in a comfortable room with one wall of windows that look out on an expansive outdoor classroom and the fields and woods that surround the school. Tables were arranged in a circle so that the 15 or so teachers and administrators could be learners together and engage in dialogue about what was most important to them.

Demonstrating “bug drawing,” pretending to follow the path of a tiny insect around the contours of an object with your eyes and your pen.

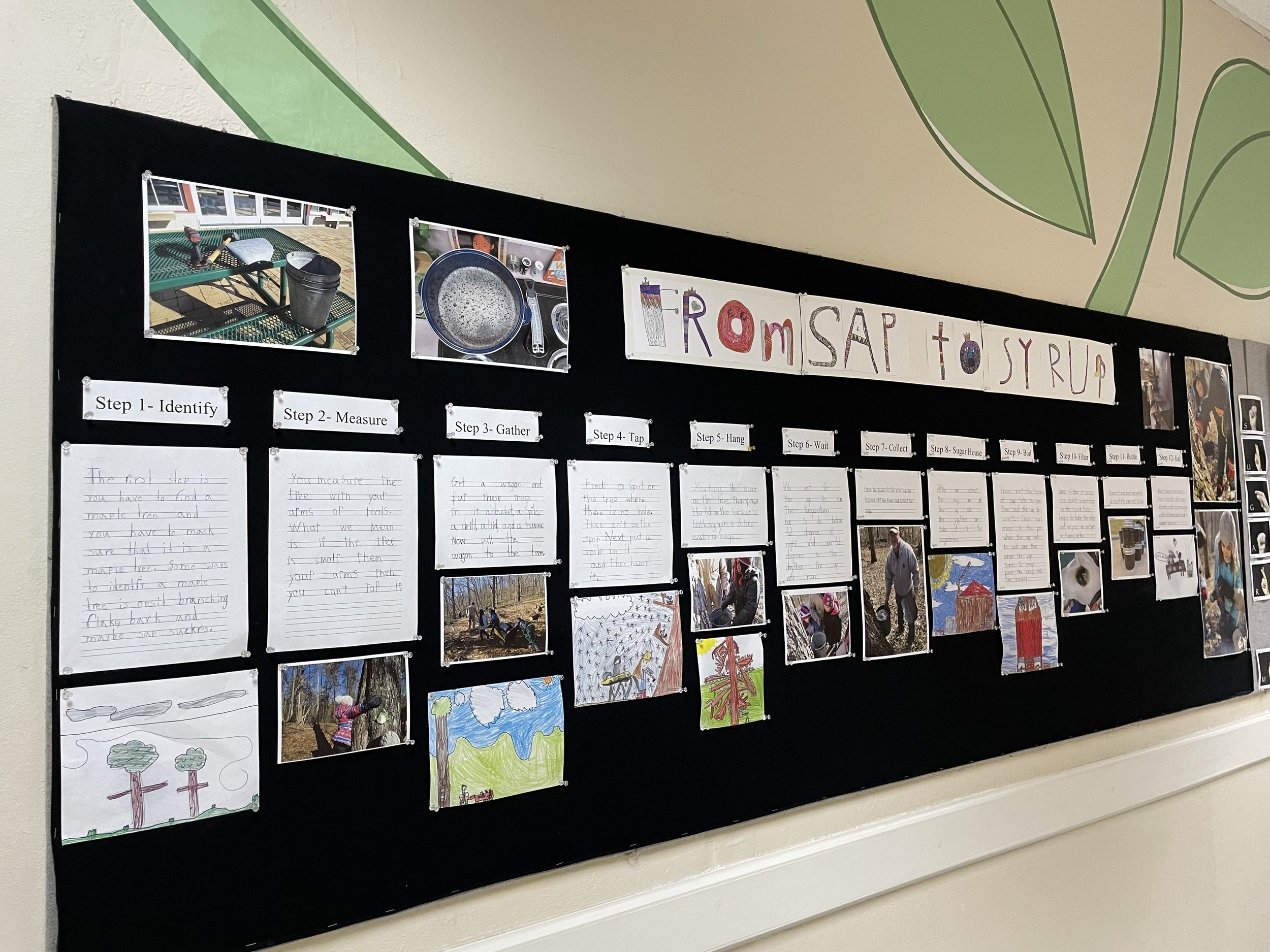

It was a joy to have a morning with Jack’s teachers and to listen to their thoughts. What struck me, more than ever, is that all these practices, that are central to the Reggio Approach, are also central to best practice no matter where the inspiration comes from. Reflecting on the morning I was reminded that all these practices are focused on developing a democratic community, where all voices matter, where all voices are heard and valued and nurtured. All voices in a school include children, teachers, parents, the larger community. Zach, the director, posed the idea of a learning community as one that grows wider and deeper and does not have an end. The idea of project work culminating in some offering to the larger community was a new idea to the teachers. This has become a central tenet of our work as Cadwell Collaborative…that learning is not for us alone, that all of us can share and offer what we learn to others in beautiful ways that become a gift.

Teacher practicing bug drawing/contour drawing with a leaf from the campus of A Child’s Place.

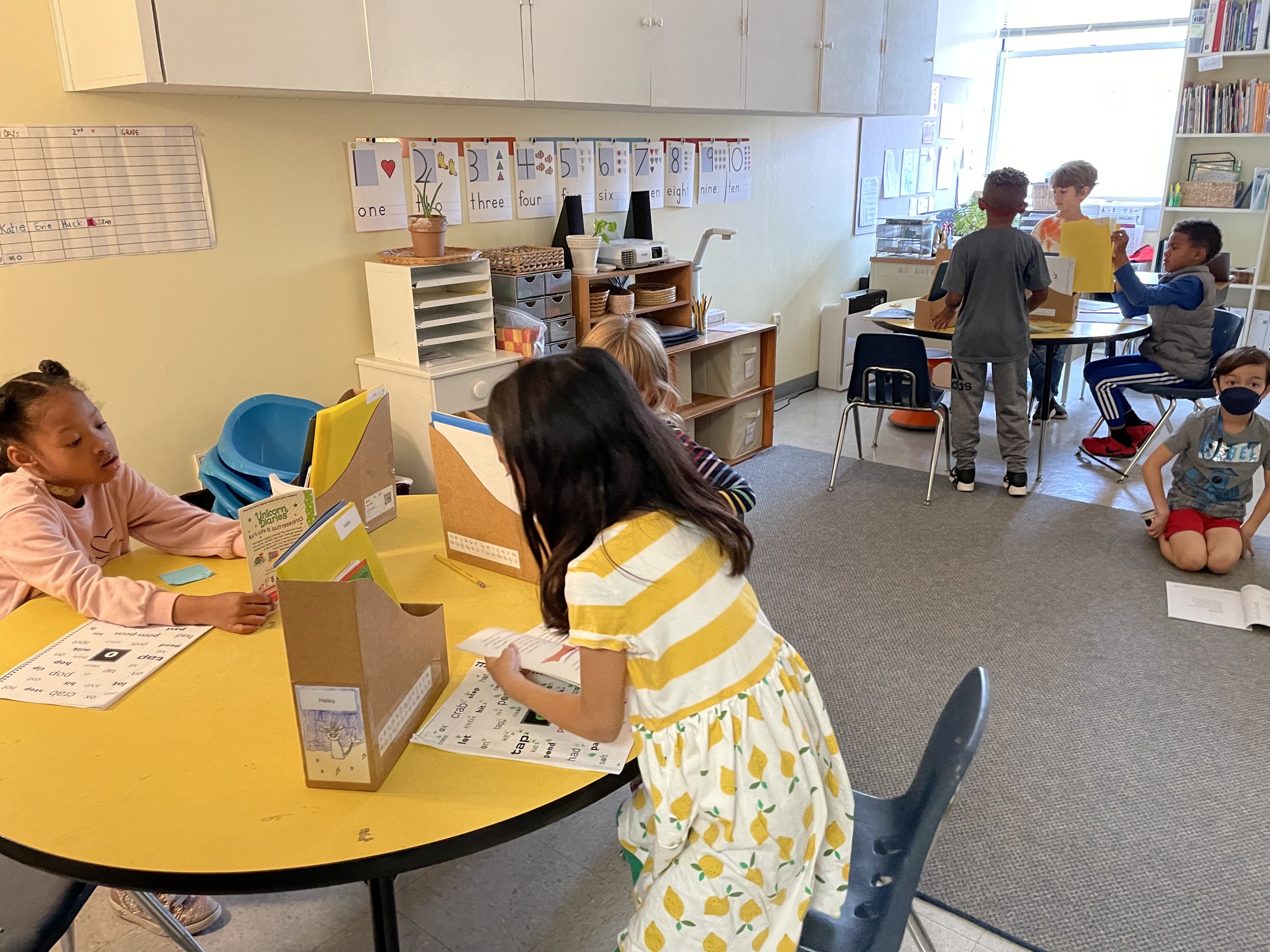

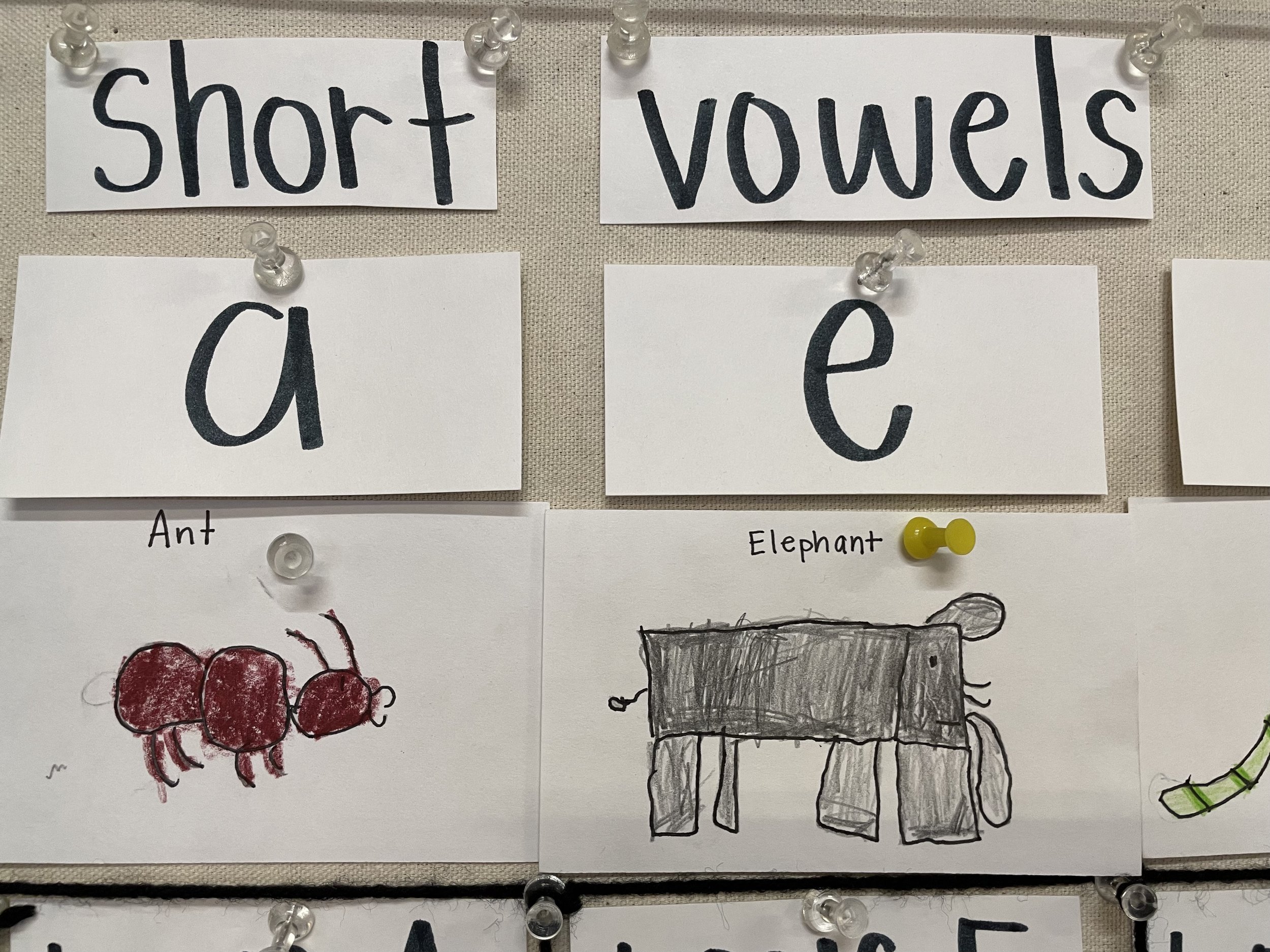

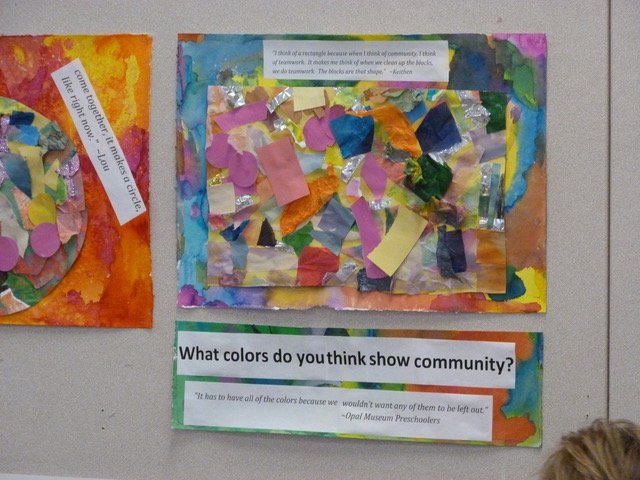

When we say that all voices matter, what is the broad and wide understanding of voice? “Voices” means children’s and adults’ words, ideas, learning, theories, perspectives, expressed in many ways and in many “languages,” as they say in Reggio Emilia…words, drawings, songs, gesture and drama, dance, numbers, sculpture….

The teachers gained a new appreciation for these foundational ideas during our morning together and so did I. I realized, once again, and in a new way, that these themes… the learning community; dialogue, conversations and listening to children; the hundred languages of children; and project work…are bound together through the idea of democracy, inclusion, equality, shared ownership, collaboration, and offering to the community.

The outdoor spaces at A Child’s Place offer endless possibilities for learning and engagement with the natural world as a part of our learning community. That morning, I shared the Tree Project from Reggio Emilia that I wrote about in chapter three of Bringing Reggio Emilia Home. This project will always be an inspiration to me. The Diana School, where I spent so many happy days, is surrounded by the trees of the Giardini Publici, the public gardens, in Reggio Emilia. A Child’s Place is surrounded by mature trees and an expanse of field and green space that is rare these days. I am so happy that Jack is at this school. I so look forward to visiting often.

Selecting leaves to draw, A Child’s Place, November, 2022

• Thanks to A Child’s Place and to Linda Littenberg for the images in this post.